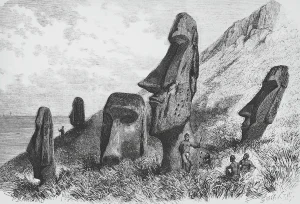

An analysis of ancient DNA from 15 former inhabitants of Rapa Nui has revealed that the island never experienced the catastrophic population collapse that has often been depicted in popular narratives, CNN reports.

This research provides new insights into the history of the remote Pacific island, located some 2,300 miles from South America.

Historically, Rapa Nui has been portrayed as a cautionary tale about the dangers of resource exploitation. In his 2005 book, “Collapse,” geographer Jared Diamond suggested that the island’s inhabitants faced ecological devastation and societal downfall due to overuse of resources. However, the findings from the latest DNA analysis, published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature, challenge this narrative, indicating that Rapa Nui was home to a sustainable population.

Researchers sequenced the genomes of individuals who lived on Rapa Nui over the past 400 years, utilizing remains stored at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The study found no evidence of a genetic bottleneck typically associated with a sharp decline in population, suggesting that the island’s population steadily increased until the 1860s, when slave raiders from Peru forcibly removed one-third of its inhabitants.

“There is definitely not a strong population collapse, like it has been argued. There was no collapse where 80% or 90% of the population died,” stated J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar, a study coauthor and assistant professor of geogenetics at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute.

The genetic analysis also revealed that the inhabitants of Rapa Nui had mixed with a Native American population, indicating contact with coastal South America between 1250 and 1430, long before Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in 1492. From 6% to 11% of their genomes showed ancestry traceable to South American ancestors, supporting previous findings from oral histories and archaeological evidence, such as the discovery of sweet potato remains — an import from South America — on the island predating European contact.

The human remains analyzed were collected by French scholar Alphonse Pinart in 1877 and Swiss anthropologist Alfred Métraux in 1935. While the exact circumstances of how these remains were taken are unclear, they form part of a larger trend of collecting artifacts and remains from colonized regions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The research team collaborated with Rapa Nui communities and government institutions to secure consent for the study and expressed hopes that the results would facilitate the repatriation of the remains, allowing the individuals to be laid to rest on the island they once inhabited.