BepiColombo’s fifth flyby sheds light on Mercury’s temperature, composition, and craters like never before, GIZMODO reports.

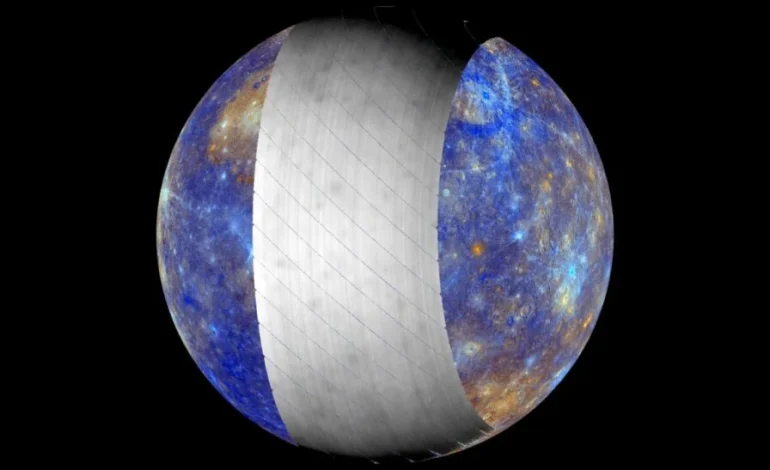

For decades, Mercury’s surface has been observed primarily through visible light, but new data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) BepiColombo spacecraft has revealed the closest planet to the Sun in a whole new light — mid-infrared, to be precise.

On its fifth flyby of Mercury last week, BepiColombo captured groundbreaking infrared images, providing unprecedented details about the planet’s surface temperature, texture, and mineral composition. Using its state-of-the-art Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS), the spacecraft offered a fresh perspective on Mercury’s mysterious, rocky terrain.

This mission, which launched in October 2018, is set to enter Mercury’s orbit in November 2026 — about a year later than originally planned. Until then, these flybys serve as crucial previews of what lies ahead.

At the heart of this breakthrough is MERTIS, a specialized instrument designed to capture Mercury’s surface in mid-infrared wavelengths. While visible light provides a simple snapshot of surface features, mid-infrared light reveals deeper insights, such as the planet’s surface roughness, mineral makeup, and temperature distribution.

“After about two decades of development, laboratory measurements of hot rocks similar to those on Mercury, and countless tests of the entire sequence of events for the mission duration, the first MERTIS data from Mercury is now available,” said Jörn Helbert, MERTIS co-principal investigator at the German Aerospace Center, in a statement from ESA.

“It is simply fantastic!”

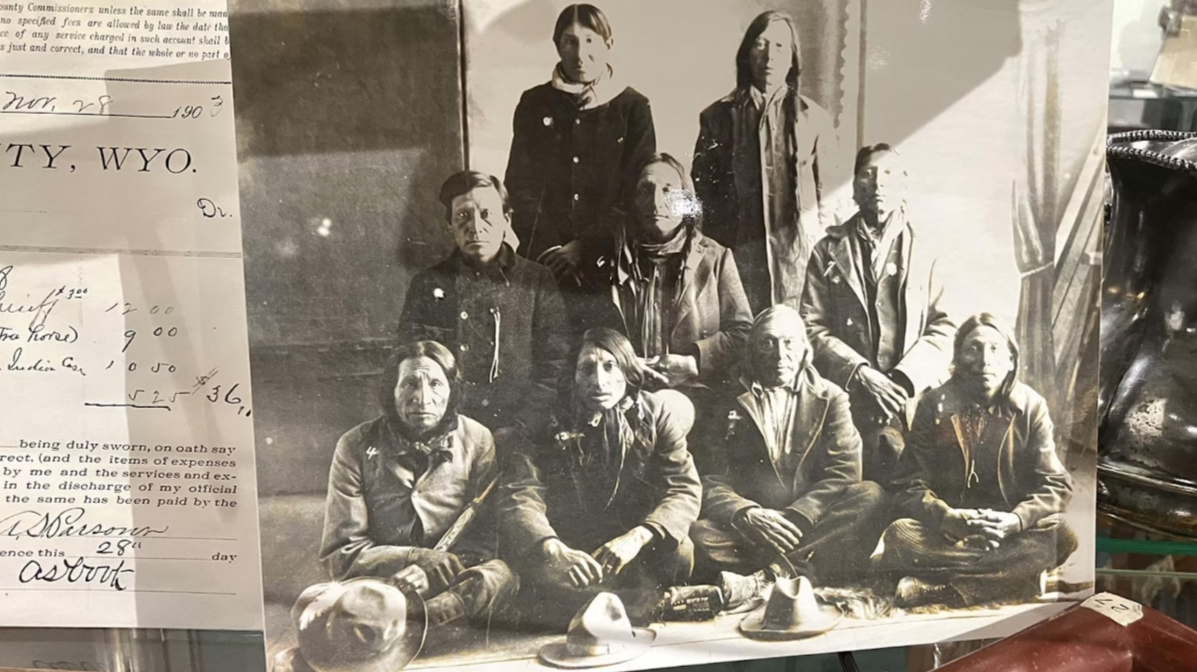

One of the most eye-catching discoveries from the flyby was the enhanced view of the Bashō Crater, a prominent impact site on Mercury’s surface. Previously captured by NASA’s Mariner 10 and Messenger missions, Bashō now appears in stunning detail under MERTIS’ infrared lens.

In visible light, Bashō is a clear, well-defined crater. But in the mid-infrared spectrum, its unique features become even more apparent, offering new insights into its composition and thermal properties.

“The moment when we first looked at the MERTIS flyby data and could immediately distinguish impact craters was breathtaking,” said Solmaz Adeli, a researcher at the German Aerospace Center’s Institute of Planetary Research. “There is so much to be discovered in this dataset – surface features that have never been observed in this way before are waiting for us.”

These revelations are just the beginning. The ability to distinguish craters and surface features at this level of detail marks a significant step forward in planetary science.

Another striking discovery from BepiColombo’s flyby is Mercury’s searing surface temperature. The spacecraft recorded a surface temperature of 788°F (420°C) at the time of the flyby — a stark reminder of the planet’s extreme conditions.

Mercury is known for its dramatic temperature swings. During the day, the surface reaches scorching temperatures due to its proximity to the Sun, but at night, when the Sun’s heat disappears, temperatures plunge to below -290°F (-180°C). Understanding these fluctuations is essential for future missions and studies of the planet’s surface composition.

By replicating Mercury-like conditions in laboratory settings, researchers can match mid-infrared “glow patterns” with specific minerals. This process helps scientists identify the types of rocks and minerals that make up the planet’s surface.

Although BepiColombo is still two years away from entering Mercury’s orbit, the data collected during its flybys is invaluable. These glimpses of Mercury’s surface provide an early preview of what scientists will be able to study in far greater detail once the spacecraft begins its full mission in orbit.

Solmaz Adeli expressed excitement for the road ahead:

“We have never been this close to understanding the global surface mineralogy of Mercury with MERTIS ready for the orbital phase of BepiColombo.”

Once in orbit, BepiColombo will be able to continuously study Mercury’s surface, offering insights into its geological history, magnetic field, and possible evidence of ancient volcanic activity.

The recent flyby of Mercury by the BepiColombo spacecraft marks a major milestone in our understanding of the Sun’s closest neighbor. With the help of the MERTIS instrument, scientists are now able to explore Mercury’s surface in greater depth, identifying craters, surface roughness, and mineral compositions that were previously undetectable.