Scientists Study 35,000-Year-Old Saber-Toothed Kitten Frozen in Siberian Permafrost

In a remarkable discovery, scientists have studied the frozen remains of a 35,000-year-old saber-toothed kitten, offering a rare glimpse into the life of an extinct predator, the Washington Post reports.

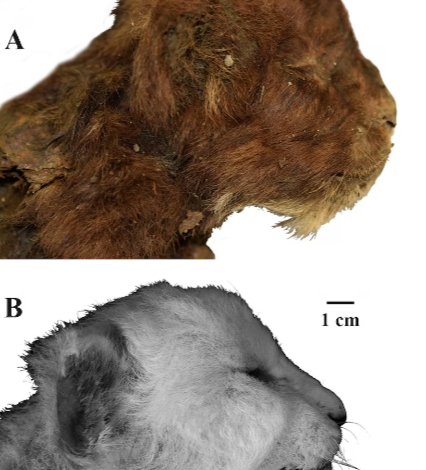

The mummified cub, found in Siberian permafrost in 2020, has been preserved in incredible detail, revealing key differences between this ancient creature and modern-day lion cubs.

The cub, estimated to be around three weeks old at the time of its death, belonged to Homotherium latidens, a species of saber-toothed cat that roamed much of the Earth during the Late Pleistocene period. The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports on Thursday, marks the first comprehensive examination of the remains of this extinct mammal.

Using radiocarbon dating, scientists determined that the cub lived between 35,000 and 37,000 years ago. The discovery is significant, as finding well-preserved remains from this era is extremely rare. Unlike previous findings of fossilized bones, the cub’s remains were covered in fur and mummified flesh, providing a wealth of information about its appearance and anatomy.

Researchers found pelvic bones, a femur, shin bones, and the frontal remains of the cub encased in ice. The cub’s body was covered in a thick layer of soft, dark brown fur, with whiskers still intact. The fur, about an inch long, is similar to that of modern-day big cats but with some notable differences. Its neck was unusually long and thick—more than twice the size of a lion cub’s neck—suggesting that the cub was already developing strength suited for its predatory lifestyle.

The scientists compared the saber-toothed kitten to a modern-day lion cub to highlight key differences. One significant finding was the cub’s broad, furry paws, which were well-suited for walking in snow. The cub’s forelimbs were nearly fully preserved, revealing sharp, curved claws—ideal for grasping and holding onto prey.

These features suggest that Homotherium latidens had a different body structure than contemporary big cats. Unlike modern cats, which are built for speed with long legs and tails for balance, the saber-toothed cat was stockier, with more powerful limbs designed for ambush attacks. Researchers noted that the cub’s strong limbs and large mouth were already adapted for this ambush-style hunting, where the animal would use its muscular forelimbs to subdue prey before delivering a fatal bite with its iconic saber teeth.

The cub’s skull and teeth also provided insights into its age. By examining the development of its baby incisor teeth, researchers were able to confirm its youthful age and compare it to that of a 3-week-old lion cub.

This discovery not only sheds light on the life of saber-toothed cats but also confirms that they were present in Asia during the Late Pleistocene period, extending their range beyond Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Saber-toothed cats, which lived for hundreds of thousands of years, eventually went extinct around 10,000 years ago, as the Ice Age came to an end and their prey dwindled. The study of this rare and well-preserved specimen offers scientists new insights into the biology and behavior of one of history’s most iconic predators.