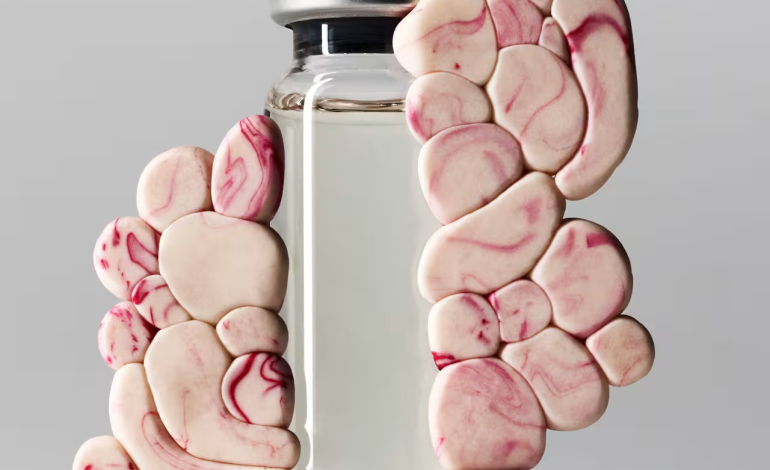

Researchers are making significant progress toward developing vaccines that could prevent cancer in high-risk individuals, the Wall Street Journal reports.

These experimental vaccines aim to train the immune system to recognize and eliminate early signs of cancer before it fully develops. While cancer vaccines are still in the early stages of human trials, they represent a growing area of research that could revolutionize cancer prevention.

The vaccines currently in development are primarily focused on individuals with inherited genetic mutations that put them at higher risk for specific types of cancer. For example, Dr. Ajay Bansal, a gastroenterologist at the University of Kansas Cancer Center, is leading trials for vaccines targeting Lynch syndrome, a genetic condition that significantly raises the risk of colorectal cancer, often at a young age.

“It’s the future of cancer prevention,” says Bansal.

This new wave of cancer vaccine research is benefiting from advancements in technology and a deeper understanding of the immune system. Companies like Moderna are also developing vaccines aimed at treating cancer or preventing its recurrence after treatment. Dr. Nora Disis, director of the Cancer Vaccine Institute at UW Medicine, signaled the potential for cancer vaccines to have a transformative impact on patient care

“It’s like the little train that could has finally reached the top of the hill,” Dr. Disis said.

Traditional vaccines, such as those for HPV and hepatitis B, work by protecting against infections that can lead to cancer. However, most cancers are not caused by infections, but by mutations in cells that allow them to blend in with healthy tissue, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize them as a threat. Researchers are now developing vaccines that target the proteins produced by these mutated cells, training the immune system to detect and attack them before cancer develops.

Cancer vaccines are considered a form of immunotherapy, a treatment approach that uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Unlike some immunotherapies that release the brakes on immune cells, cancer vaccines are designed to boost the immune response and direct it toward cancer cells.

“Cancer cells and even pre-cancer cells know how to hide from the immune system… It needs that help from a vaccine,” explains Dr. Neeha Zaidi, a medical oncologist at Johns Hopkins.

Zaidi’s team is testing a vaccine targeting mutated proteins linked to the KRAS gene, which is associated with lung, pancreatic, and other cancers. In early trials, the vaccine generated promising immune responses in participants at high risk for pancreatic cancer. Other approaches, such as those using mRNA and DNA technology, are also being tested to stimulate immune responses against cancer-related proteins.

Sara Walker, a participant in a Penn Medicine trial, received a DNA vaccine aimed at people with inherited BRCA gene mutations, which increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancers. Walker, a mother of three, underwent preventive surgeries to lower her cancer risk and is now hopeful that the vaccine could allow future generations to avoid such drastic measures.

“To know my girls would not have to have their breasts removed, their ovaries removed, that’s life-changing,” she says.

While early trials are primarily focused on safety and immune response rather than cancer prevention, researchers are optimistic that these vaccines could one day allow people to reduce their cancer risk without undergoing invasive procedures. Dr. Robert Vonderheide, director of Penn Medicine’s Abramson Cancer Center, suggests that this work could eventually lead to vaccines for a broader range of cancers, and even the possibility of a universal cancer vaccine.

Despite the progress, some researchers are cautious about the prospect of a single vaccine for all cancers, given the complexity of the disease.

“We don’t have a universal flu vaccine, let alone an all-infectious-disease vaccine,” says Dr. G. Thomas Budd of the Cleveland Clinic.

However, he envisions a future where people may receive specific vaccines to target their biggest cancer risks.

Ongoing research continues to explore vaccines for various types of precancerous conditions. For instance, Dr. Olivera Finn from the University of Pittsburgh is testing a vaccine targeting the protein MUC1, which is overabundant in several cancers, including breast and colon cancer. While still in early stages, these efforts could lead to new preventive measures that dramatically reduce cancer incidence.