Despite its reputation for rapid social progress, Ireland’s parliament lags behind its Western European counterparts in gender diversity, ranking last in the region, Bloomberg reports.

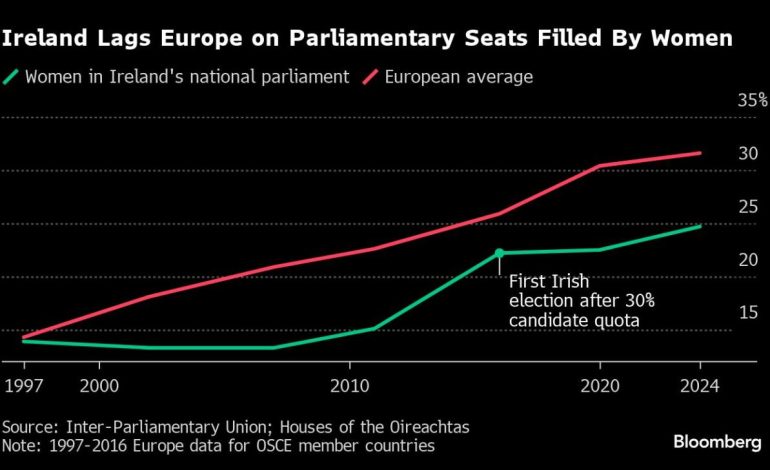

Even after increasing its gender quota for the recent November 29 general election, women hold only 25% of the 174 seats in the Dáil (parliament), falling significantly short of the 37% average across Western European parliaments and the 32% average for Europe as a whole, according to a Bloomberg analysis of Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) data.

This underrepresentation is a setback for Ireland, a nation that has shed much of its traditional Catholic conservatism and experienced significant economic growth since the 1990s. While Ireland boasts one of Europe’s wealthiest economies and a budget surplus, this prosperity has not translated into increased female political representation.

In fact, Ireland’s progress has even reversed some earlier gains. The country held relatively high levels of female representation in the 1990s, including electing its first female president, Mary Robinson, in 1990. However, it began to lag behind other European nations in the early 2000s. While other countries implemented affirmative action measures, Ireland only introduced a binding 30% quota for political parties in 2012, later raising it to 40% for the recent election.

According to Fiona Buckley, a senior lecturer at University College Cork, this inaction stemmed from a lack of serious conversation about political reform until after the 2008 financial crisis. She points to the contrast with countries like Belgium, which introduced legislation in 1994 to increase female participation in politics.

Newly elected Labour MP Marie Sherlock highlighted a potential paradox: while Ireland has made significant strides in social legislation, such as the 2015 gender recognition bill, the current political climate might hinder the passage of similar reforms. She also cited the recent defeat of referendums aimed at updating constitutional language on women and family, a surprising setback considering the country’s legalization of same-sex marriage in 2016 and the repeal of the 8th amendment on abortion in 2018.

The National Women’s Council of Ireland attributes the low representation to the challenges faced by women entering local politics, describing it as “the preserve of those with the lowest care load.” Sherlock’s own experience running for local office while pregnant with her third child underscores this difficulty. The Council advocates extending the gender quota to local elections to lower this significant barrier to entry.

Despite the setbacks, the 40% quota did result in the highest ever proportion of female MPs in the Dáil, a modest improvement of seven seats from the 2020 election. While acknowledging progress, Buckley notes that it took 14 years and three electoral cycles to achieve what previously took 37 years and 10 cycles.