Can a Twice-Yearly Shot Help End AIDS? The Challenge of Global Access

A groundbreaking HIV prevention shot, described as the closest the world has ever come to a vaccine for AIDS, could play a pivotal role in ending the epidemic, the Associated Press reports.

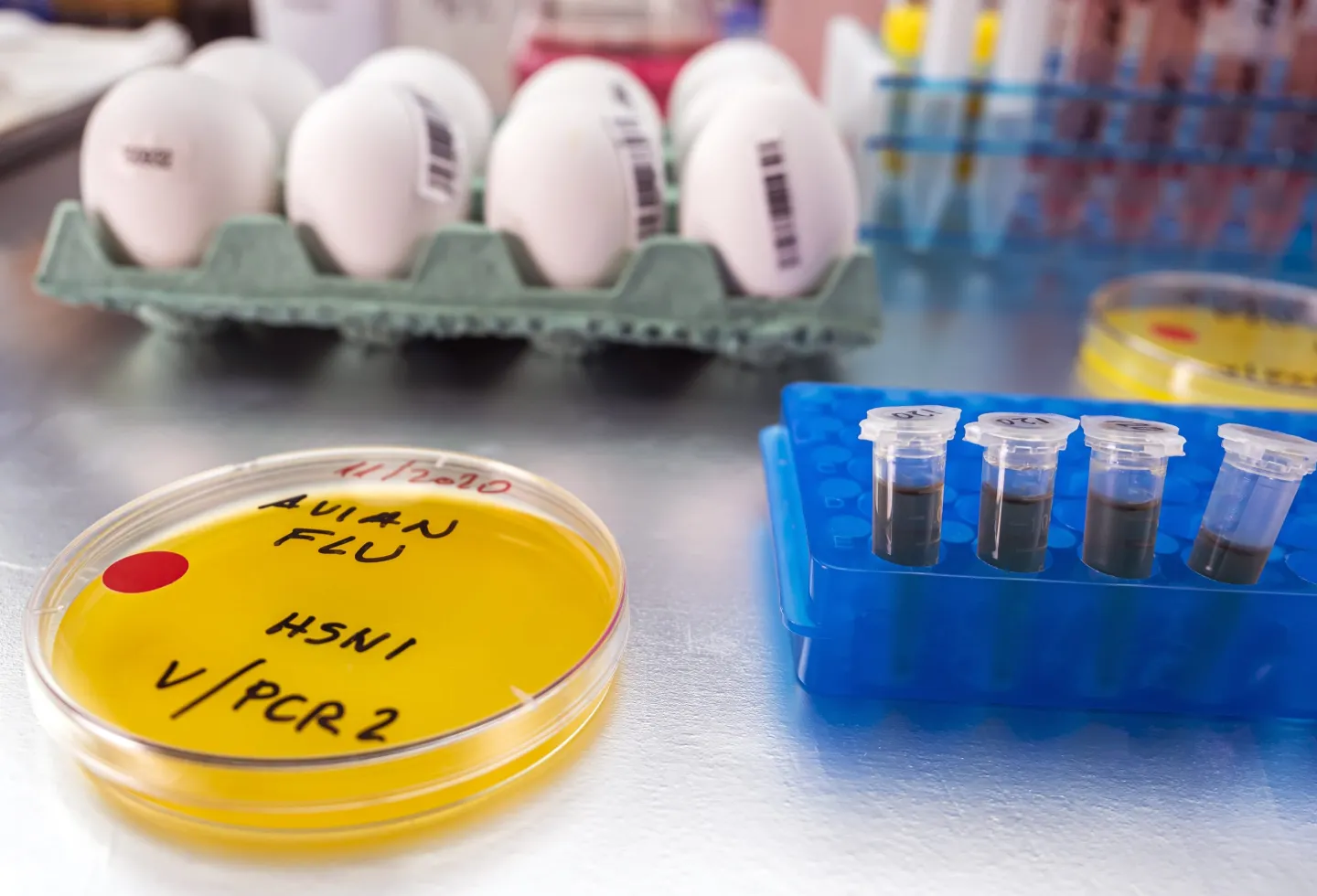

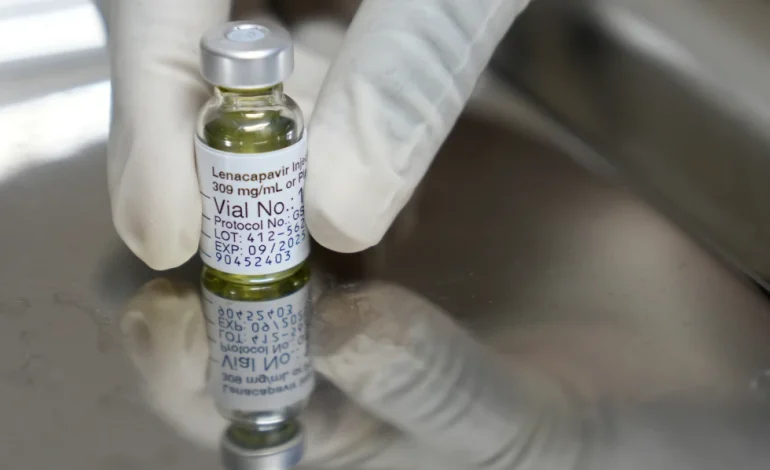

The twice-yearly shot, developed by Gilead Sciences and known as lenacapavir, has shown impressive results, with studies demonstrating its 100% effectiveness in preventing HIV infections in women and nearly identical results in men. However, questions remain about whether the shot will reach everyone who needs it, particularly in regions where HIV rates are rising.

Lenacapavir, sold under the brand name Sunlenca, is already used to treat existing HIV infections in various countries, including the US, Canada, and parts of Europe. Gilead announced that it will make generic versions of the drug available in 120 countries with high HIV rates, including many in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean. However, it has excluded Latin America—where HIV rates are increasing despite being lower compared to Africa—from this generics deal, sparking concern among public health advocates.

Winnie Byanyima, the executive director of UNAIDS, praised the drug as a significant advancement in HIV prevention but highlighted the importance of making it accessible in all affected regions.

“This is so far superior to any other prevention method we have, that it’s unprecedented,” Byanyima said.

He emphasized that the success of the global fight against AIDS hinges on the widespread use of lenacapavir, especially in at-risk countries.

UNAIDS’ recent World AIDS Day report highlighted that AIDS-related deaths have reached their lowest point since 2004, showing that global efforts to combat the virus have made considerable progress. However, with over 630,000 AIDS-related deaths last year, the report noted that the world is at a “historic crossroads” and has a unique opportunity to end the epidemic if the right strategies are implemented.

Experts say the twice-yearly shot could be a game-changer for marginalized groups, including gay men, sex workers, and young women—populations often reluctant to seek care due to stigma or fear of discrimination. The ease of administering the shot—just two visits a year—offers a simple, effective alternative to daily pills or other prevention methods that may be more difficult to adhere to for those at high risk of HIV.

Luis Ruvalcaba, a 32-year-old man from Guadalajara, Mexico, who participated in the study, shared how the shot could be a lifeline for those reluctant to ask for daily prevention pills due to stigma.

“In Latin American countries, there is still a lot of stigma, patients are ashamed to ask for the pills,” said Dr. Alma Minerva Pérez, a researcher involved in the study.

Despite the promise of lenacapavir, the lack of access to affordable versions of the drug in Latin America is a growing concern. Countries such as Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, which have higher HIV rates than many others in the region, are currently excluded from the generics deal. In response, advocacy groups from Latin American countries, including Peru, Argentina, and Ecuador, have called on Gilead to expand the availability of the generic version of Sunlenca in the region.

Health experts argue that access to this shot is essential for combatting the rising HIV rates in Latin America, where infections among marginalized communities, including gay men and transgender individuals, are reaching alarming levels. Dr. Chris Beyrer, director of the Global Health Institute at Duke University, emphasized that Latin America’s HIV crisis represents a public health emergency and that solutions like lenacapavir are vital for addressing the region’s needs.

While Gilead has committed to helping enable access to HIV prevention and treatment options in the hardest-hit countries, questions about the availability of affordable treatment in Latin America remain unresolved. Mexico has already made strides by providing free daily prevention pills, but the cost and availability of lenacapavir for prevention are still uncertain.

In addition, other HIV prevention options, like the bi-monthly Apretude shots, developed by Viiv Healthcare, are also available in limited regions, often at a high cost. Some experts have called for countries like Brazil and Mexico to consider issuing compulsory licenses, a strategy that has been used in the past to increase access to life-saving medications in health crises.

Dr. Salim Abdool Karim, an AIDS expert in South Africa, underscored the importance of reaching everyone in need of lenacapavir, saying:

“The missing piece in the puzzle now is how we get it to everyone who needs it.”